By Joe Chidley, Managing Editor, Canadian Family Offices

Family offices—private advisory firms that manage the financial and, often, non-financial affairs of ultra-high-net-worth families—are an increasingly significant presence in the global financial landscape, driven by secular trends in wealth creation and intergenerational wealth transition. According to a recent study by Deloitte Private, family office assets under management (AUM) will by 2030 grow to US$5.4 trillion—a 73 per cent increase over 2024. In terms of global financial footprint, that would make family offices rivals to the hedge fund industry.

As a result, family offices are becoming important forces in capital deployment and formation. At least on a global basis, where estimates of the number of family offices range from a little more than 8,000 (according to Deloitte Private) to 20,000 in other surveys, the impact of the families they support, how much they invest and where they invest will continue to grow.

But what is happening in Canada? Here, the picture is far less clear. Compared to the United States, Europe and Asia, family offices in Canada are generally considered a still-nascent industry, which goes some way towards explaining the dearth of country-specific data. Anecdotal estimates of the number of Canadian single-family offices (those that, as the name implies, serve only one family) range from a few dozen to the hundreds. As for the other branch of the family office ecosystem, multi-family offices (MFOs), which are typically profit-seeking enterprises that serve multiple clients, the numbers are equally murky: a list compiled by Canadian Family Offices in 2023 included 81 firms, but there were—and now are—almost certainly many more.

To fill at least some of the knowledge gaps about an ecosystem that is still growing and rapidly evolving, Canadian Family Offices has for the past two years conducted a survey of multi-family offices—the only one of its kind in Canada. Our recently released latest study, The Multi-Family Office Landscape in Canada 2025, is based on a survey of nearly 80 MFOs across the country, and it includes several findings that point to trends in how and where MFOs are investing, what their concerns are, and specifically their attitudes towards alternatives investments, including venture capital and private equity.

Asset allocations: Staying the course

Wealth management is a core function of family offices, and they tend to be long-term investors. Rather than targeting quarterly or annual returns, they typically strive to achieve asset allocations for their client families that will grow and endure across generations. As well, wealth preservation is often a key mandate for family offices, supporting a preference for assets that are viewed as less risky.

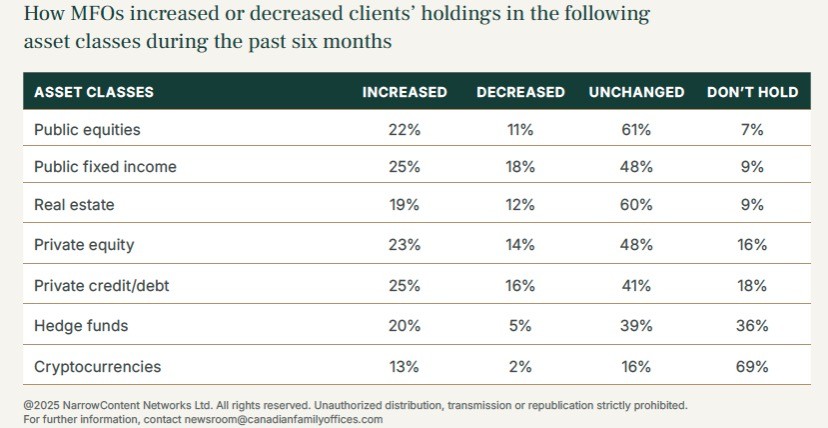

Those characteristics are certainly borne out by our study results. We asked MFOs whether they had increased or decreased their allocations to a wide range of asset classes over the past six months. In every category—public equity and fixed income, private equity and credit, real estate, hedge funds and cryptocurrency—the most common answer was that MFOs had not changed their clients’ holdings. We may also infer family offices’ risk tolerance based on the extent to which they do not hold a particular asset class at all. For example, while nearly all MFOs surveyed had exposures to publicly traded equities and fixed income, as well as real estate, more than a third do not hold hedge funds and more than two-thirds have no holdings in cryptocurrency.

Exposure to alternative assets

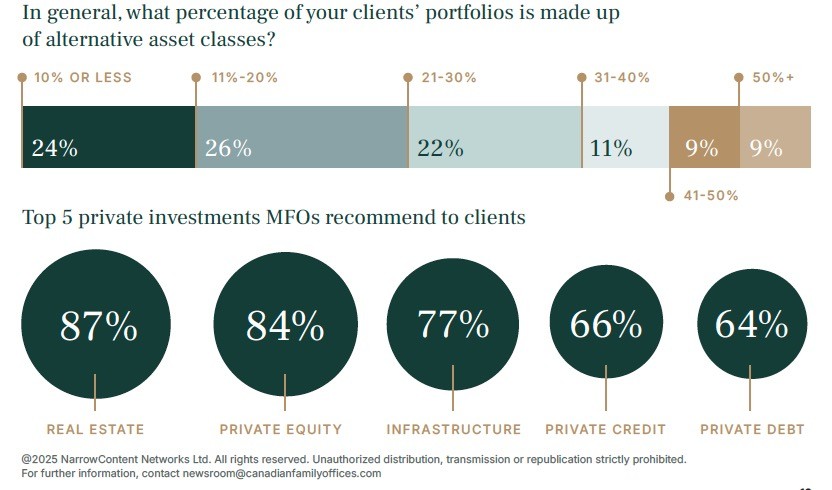

On a global basis, family offices are heavily invested in alternative investments. BlackRock’s 2025 Global Family Office Report found that alts comprise 42 per cent of family office portfolios, while the UBS Global Family Office Report 2025 claimed that alternatives make up 54 per cent of U.S. family office portfolios. The reasons are clear in alts’ potential for lower volatility and greater diversification, as well as their asymmetrical return profile.

Most Canadian multi-family offices also allocate to alts in one form or another (real estate is their No. 1 alternative holding, followed by private equity and private credit), but the level of that allocation seems to lag global counterparts. In our survey, alternatives account for less than 40 per cent of holdings in 83 per cent of Canadian MFO client portfolios, and for less than 50 per cent in more than 90 per cent of MFO portfolios. In nearly one-quarter of MFO client portfolios, alternatives account for 10 per cent or less of holdings.

To get a deeper read on MFOs’ approach to alternatives, we asked which private asset classes they recommend to clients. Not surprisingly, real estate was the top choice, closely followed by private equity (84 per cent). Meanwhile, infrastructure was recommended by more than three-quarters of respondents, and private credit by nearly two-thirds. Notably, however, venture capital was recommended by just 44 per cent of MFOs—down marginally from last year.

Why the relatively low level of recommendation for venture capital? Perhaps, given the strong performance of public markets and credit this year as interest rates decline, family offices saw better potential for risk-adjusted returns in more traditional asset classes. Perhaps, too, their conservative approach to risk and wealth preservation is at play here.

MFOs’ top concerns

With tariff turmoil and geopolitical conflict dominating headlines this year, one might expect those issues to be top-of-mind for Canadian MFOs. But when we asked them about their top concerns, their most cited worry had nothing (or little) to do with volatility out of Washington or souring U.S.-Canada relations.

Instead, Canadian tax policy was cited by 42 per cent of survey respondents as their top concern. It was also the most commonly cited concern worry in last year’s study. That suggests MFO leaders see little improvement in Canadian tax policy with a new government in place in Ottawa. As well, the tax environment might be one factor in their relatively modest interest in venture capital in their client portfolios.

The second most common concern this year may also come as something of a surprise: AI and cybersecurity issues. Those were ranked near the bottom in last year’s survey, and the turnaround suggests that awareness of cyber risk among family offices has grown significantly in 2025.

Beyond the 49th Parallel?

At a high level, Canadian MFOs clearly seek investment opportunities with a global outlook. Eighty-four per cent of respondents in our survey said that non-Canadian assets comprise more than 30 per cent of their client portfolios, including nearly 40 per cent who said that global investments make up more than half of portfolios.

Where are those investments? American assets make up a sizable proportion of MFOs’ non-Canadian investments, comprising between 30 and 50 per cent of clients’ non-domestic holdings for more than half of survey respondents. Yet the landscape may be shifting. In our survey, more than two in five MFOs said that they intend to reduce allocations to the U.S. over the next 12 months. Almost one in five said they planned to increase exposures to emerging markets, while more than 40 per cent said that they intended to increase allocations to developed markets outside the U.S., such as Europe and Japan.

The Multi-Family Office Landscape in Canada 2025 offers plenty of other insights about MFOs, including size, location, assets under management and revenue models. While our study is intended to be directional rather than definitive, our hope is that it will help address a long-standing information gap and contribute to a deeper understanding of this rapidly evolving corner of the Canadian financial ecosystem.